|

|

METHODOLOGY

AND RESULTS

[ Neolithic, Early and Middle Chalcolithic | Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age | Second Millennium | Mid-first Millennium | Tumuli | Hellenistic | Roman to Byzantine | Selcuk | Other Results | Major Conclusions | References ]

The main potential routes were followed, as far as it was possible to do so by car. Information was sought in towns and villages to supplement that provided by Mr Özcan, Director of the Yozgat Museum and what little had been gleaned from maps and publications. Progress was plotted with a mobile GPS receiver that was magnetically attached to the top of the car and carried to sites off the road. Sites and views were recorded with a digital camera, presented to the Kerkenes Project by TAI in 1997, and by traditional black and white and colour slide photography. Both the GPS and the digital camera could be downloaded into a lap top in the field. Pottery was collected and examined on each site, only a handful of sherds being retained for future drawing as evidence to support major conclusions. The idea of taking photographs of diagnostic sherds in the field was abandoned because it was quickly realised that useful photographs would have entailed washing the material. |

|

|

Neolithic, Early and Middle Chalcolithic No trace of neolithic or early and middle chalcolithic settlement was found. On one site, Kale Tepe Höyük (see below) a late chalcolithic level appears to rest directly on bed-rock. It would thus appear that settlement sites in the broad valleys, like those in the Kanak Su basin to the south, are probably buried beneath alluvium. While very intensive survey might produce evidence for these periods on the higher valley terraces, and perhaps elsewhere on higher ground, it is extremely unlikely that any useful settlement pattern would come out of traditional intensive survey on foot because of later geomorphological alteration to the landscape. These changes include severe erosion on the slopes and high ground, infilling of valleys and movement of stream and river beds within the valley floors.

|

|

|

Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age One site of considerable interest was visited, Kale Tepe Höyük, just north of Aydincik. Here villagers have been digging into the side of the mound to create terraced fields. In so doing they have exposed two highly burnt and well preserved levels, one apparently directly on top of the other. The lower, resting directly on bed-rock where this is exposed, would appear to be late Chalcolithic (Alisar "fruit stands"), the second some sort of EB II, according to current sparse knowledge of the ceramic sequence for the region. Exposure of the lower level has revealed a room with burnt mud-brick walls and floors with a row of charred roof beams just above the floor. Other charred timbers are also visible in the cuts. It is hoped that Prof. Peter Kuniholm will be able to extract samples from these beams for dendrochronological dating which would provide new and very welcome evidence for these periods. EBA settlements of varying size and depth are widespread in a variety of locations. Interestingly, one small EBA site was located by chance on a high and exposed hill top. This site replicates evidence from the Kerkenes Dag where there are a number of small hill top sites. These sites perhaps represent some form of seasonal upland exploitation and may be related to deforestation and resultant erosion. From a distance these sites resemble the tumuli that are scattered along ridges, on hill tops and knolls.

|

|

|

In the grounds new mosque at Asagi Karakaya Köy, about 4 km north-west of Kusakli Höyük, a large carved and smoothed granite block with a row of four drilled dowel holes was discovered. This block is clearly of Hittite workmanship from a major public building, presumably a temple. The stone was said to have come from the old mosque in the village when that was demolished (?in the 1960s). No further stones of this nature were located. The block surely came from Kusakli Höyük and adds further evidence that it was a Hittite city of some importance, almost certainly Zippalanda. There is second and first millennium material at Kale Tepe Höyük, as might be expected, but the upper level and the top were under dense cultivation, thus it was not possible to gauge the extent and importance.

|

|

|

Surprisingly, no eighth-seventh painted material akin to Alisar IV was found. I have no explanation for this absence. It may be present beneath the crops at Kale Tepe Höyük, but if so it would be sparse. Two mid-first millennium sites, presumably contemporaneous with the city on the Kerkenes Dag, guard the approaches to the pass over the Dagni Dag between Eymir and Aydincik. The first is on a steep bluff where the narrow rocky valley of the Eymir Çay opens out to rolling foothills below the pass. The other, in a similar position on the north side of the pass, is Kale Tepe Höyük. The juxtaposition of this pair of sites surely indicates that the route northwards from Kerkenes took this direct line in the Median and Achaemenid periods. Our pottery sequence at Kerkenes is not yet secure enough to be certain that these two sites were occupied in the Median period, but since both have Achaemenid material and material that closely resembles that from Kerkenes, the conclusions regarding the route seem secure enough. It may be significant that the first of these sites did not have any Hellenistic pottery, either fine wares or the so-called Galatian ware.

As in the vicinity of Kerkenes Dag, there are tumuli on ridges, hill tops, knolls, höyüks and plains. Dating is unclear, some are known from excavation to be Achaemenid, none certainly earlier but this needs confirmation. There is said to be a tumulus with an ashlar chamber and dromos on the top of the Dagni Dag.

|

|

|

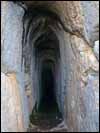

One Hellenistic site, already known in the literature (Atalay and Ertekin 1986), was visited on top of the east side of the Kazankaya gorge. At the base of the gorge, on the other side and within Çorum province, is a Hellenistic rock relief. We could see no apparent connection between these two sites apart from their apparent date. The site that we visited comprises a long, sloping rock-cut tunnel with neatly cut steps at the upper end. The tunnel is cut into limestone and was obviously intended to reach water or to end in a rock-cut cistern. To the evident surprise of the builders the limestone suddenly gave way to highly fractured volcanic rock. In a desperate attempt to find water a number of low and irregular passages were hacked out of the volcanic material in various directions before the whole scheme was abandoned. On the steep jagged rock above a small square tower like structure of evidently Hellenistic drafted masonry was constructed, but nothing further that we could see in the rapidly fading light. A few fragments of mortar and tile attest some later activity in the vicinity. The site is surely Pontic castle intended to protect passage along the top of the eastern side of the Kazankaya Gorge. It seems most likely that the original scheme to construct a substantial castle was abandoned when it proved impossible to secure a supply of fresh water.

|

|

|

No particular effort was made to visit and record sites of these periods, many of which are flat. Almost every modern settlement has one or more Byzantine grave stelae, the majority of which are inscribed. Besides the flat, rural sites three sites of some note were recorded. Sebek, high on the north slope of the Dagni Dag, above Aydincik, is said to have been monastic. Little remains beyond a few scattered foundations amongst the bushes. A site in the bottom of the Kazankaya Gorge, on the left bank of the Çekerek Irmak has a mortared defensive wall on the south side that was once carried across the river. Although it is called a Kale, the precise nature and function of the site is elusive. Preserved logs surviving in the defensive wall could suggest that it is a later construction than the buildings behind it. Kale Tepe, Kayakisla has a Byzantine wall across the south end. The mortar and the surface pottery are reminiscent of Keykavus Kale on the Kerkenes Dag, to which it may be related.

|

|

Selcuk At the foot of Kale Tepe Höyük, Aydincik, are remains of a substantial

Selcuk period structure, presumably a caravanserai. Little remains in

situ, the interior being beneath field, the outer walls forming field

boundaries. It would not be possible to recover much of the plan. The

location, however, underlines continuing use of the north - south route.

|

|

|

|

There does not seem to have been a major site in the vicinity of Çekerek town. The site at Aciacihöyük is modest. The course of the modern main road between Sorgun and Çekerek (the Samsun-Kayseri road) does not follow an ancient route. The modern road from Alaca to Çekerek diverges from the ancient route somewhere near the sharp turn in Çekerek Irmak, the natural route following the river valley in the general direction of Zile and Masat Höyük. A route along the Çekerek Irmak from just south of Çekerek itself north-eastwards towards Zile is perfectly possible, but no evidence was seen to suggest that it was of particular importance at any period. The southern continuation of this route would probably have more or less followed the course of the river rather than the main road, but this region fell outside the area of our survey.

|

|

The principle objectives of the survey were achieved and no further field work in the region covered is contemplated in the immediate future. Preliminary results are to be published on the Kerkenes Project Web Page and in the Sonüçlar. The principle results will be incorporated in the forthcoming monograph on the Kerkenes Project. Detailed evidence will be combined with other results from the Kerkenes Regional Survey and included in specialist papers as appropriate. It is hoped that Prof. Kuniholm will be able to build on the discoveries at Kale Tepe Höyük in the summer of 1998. 1. The Hittite route from Küsakli Höyük (Zippalanda) to Ortaköy (Sapinuwa) more or less followed the line: Gurpinar, Külhöyük, Kayakisla Kale Tepe, taking the modern pass over the Dagni Dag range (their being no viable alternative), Kale Tepe Höyük and thence crossing the Alan Dag somewhere west of the Kazankaya Gorge. 2. The mid-first millennium route between Kerkenes (Pteria) and Sinop (Sinope) followed the same route, probably crossing the Alan Dag immediately west of the Kazankaya Gorge and thence proceeding north-westwards towards Amasya. This is much easier and more direct than the course of the modern road from Sorgun via Çekerek to Zile. 3. This direct route north would have been very difficult if not impossible in winter. Its major importance is probably restricted to the brief life span of the Median city of Pteria on the Kerkenes Dag when it would have facilitated contact between the Medes and Greek colonies on the Black Sea, notably Sinope. Herodotus knew that Pteria lay due south of Sinope, the only place that he mentions in connection with Pteria. 4. The Dagni Dag appears to form the natural border between Cappadocia and Pontus. 5. Major intensive survey of the region covered would produce a mass of detail but perhaps little of wider significance for the prehistory of the northern plateau. Because of crop cover, intensive survey would involve much field walking in both early spring and in autumn over several seasons. It would be essential to combine any more intensive traditional survey with a detailed study of the geomorphology and the creation of predictive models that took into account changes to the landscape over the last 12,000 years.

Abbreviations are those used in Anatolian Studies. Atalay, E. and Ertikin, A. 1986. "Çorum Yöresinde Yeni Bulunan Kaya Kabartmasi", Eski Eserler ve Müzeler Bülteni 8 (T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanligi), 19-26. Gorny, R. L. In press. "Zippalanda and Ankuwa: the Geography of Central Anatolia in the Second Millennium B.C.", JAOS. Gurney, O. R. 1995. "The Hittite Names of Kerkenes Dag and Kusakli Höyük", AnSt XLV, 69-71. Özgüç, T. 1978. Masat Höyük Kazilarive Çevresindeki Arastirmlar: Excavations at Masat Höyük and Investigations in its Vicinity, Ankara (TTK Yayinlari, V Dizi - Sa. 38). Özgüç, T. 1982 Masat Höyük II, Ankara (TTK Yayinlari, V Dizi - Sa. 38a). Przeworski, S. 1929. "Die Lage von Pteria". Archiv Orientalni I, 312-315. Summers, G. D. 1997. "The Name of the Ancient City on Kerkenes Dag in Central Anatolia", JNES 56, 1-14. Restel; M. 1979. Studien zur frübyzantinischen Architektur Kappadokiens, TIB 3.2, Wien. Pl. 127 Sivrihisar, Kizil Kilise. Yalçin, S. 1995. "Kümbetova'da Hititler", Aydincik Belediyesi Bülteni 2, 17-20. Reprinted from Peron Magazin Dergisi, Eylül 1988.

|